Can the Rocky film franchise be read as a feminist text?

Lover Or Fighter is an essay I wrote in 2012 about the Rocky movies and a potential link between them and feminist theory.

Far-fetched? A strange combination? Read and decide for yourself.

Lover Or Fighter:

The Performance Of Masculinity In The Rocky Series

Looking at The Male Body

Although the male body has long ceded its position as a comfortable resting place of the desirous gaze in the fine arts, that is not to say that it has been removed from public view; there is one location where it has hollowed out a secret niche – the popular cinema.

In the split between elite and popular culture, the male body has been firmly grasped by the latter and held aloft for public consumption by movie-goers and subsequently, by advertisers capitalising on the imagery spawned by the cinema.

Why a ‘secret niche’?

This gazing at the male body is sanctioned by the spectacle of the action film, yet, is burdened by the audience’s complex relationship to the violence and eroticism inflicted on the male body in these films. Hollywood blockbusters of the 1980s carried the extreme end of masculinity’s muscular mask from the relative obscurity of the bodybuilding subculture to international fame, so that the hero was “defined and determined by a focus on the body.” (Jeffords, 1994:53).

In examining popular culture’s representation of the muscular male body, it may be useful to consider a film series which has spanned a period of some thirty years, and the changing body of its hero, Rocky Balboa.

Rocky

The release of Rocky in 1976 met with critical acclaim, winning three Academy Awards, with nominations in seven other categories. The film was propelled into the popular imagination and the character of Rocky became one of the most heavily cited and enduring pop culture figures of the last century.

This essay will focus on the performance of the series’ complex masculine ideology, its use of the male body as a receptacle for the erotic gaze, and the meanings of the physical transformation of Rocky’s body over the series.

Much could be said about the phenomenon of seriality within the most popular films of the 1980s and 1990s, but that is more than may be allowed for at the present.

Masculinities

Just as this character’s performance of manliness has spawned countless copies and tributes, so was it formed as a copy of previous manifestations; boxers such as Chuck Wepner providing the inspiration, and Rocky Marciano the name.

Although a movie which uses boxing as its narrative vehicle may easily be misconstrued as being fixated on a single-sided masculinity, the first two films (separating these from the latter for reasons to be expanded upon) depend heavily upon conflicts within masculine ideologies for their success.

Let’s assume the traditional anthropological/cultural standpoint of women being associated with nature and men with culture. Rocky purposefully turns this around, giving us a character emblematic of natural masculinity.

His body is his means of providing materially, and is also his means of expression: through boxing alone he experiences success, proving to the world that he is more than ‘another bum from the neighbourhood’.

His speech is slow and slurred, although he speaks most when trying to seduce Adrian, the shy girl from the pet store; however, his words only go so far. In the romantic scenes within his apartment, it is his body to which she responds. He is thus portrayed as a natural man: genuine, without artifice and ultimately irresistible.

This focus on Rocky’s body introduces the contradictory qualities of the male bodybuilder hero. Tasker (1993: 78) describes the way in which the bodybuilder is an unnatural, manufactured product, existing precisely to be looked at.

The bodybuilder as a feminised man

Since ‘real men’ are not obsessed with their looks, this narcissistic element of performance marks the hyper-masculine bodybuilder as a feminised man.

“If, for some, the figure of the bodybuilder signals an assertion of male dominance, an eroticising of the powerful male body, for other critics it seems to signal an hysterical and unstable image of manhood… it is clear that both active and passive, both feminine and masculine terms, inform the imagery of the male body in the action cinema.” (Tasker, 1993: 80)

This leads us to the role of the feminine. Adrian is the voice of reason and intelligence – culture – in Rocky II – urging her newly bourgeois husband not to spend his money carelessly. Rocky ignores her advice, desiring to be seen as a financial success. As a result he finds himself eventually having to sell his ostentatious acquisitions to men who are, although physically and morally weaker, more powerful.

Feminine power and weakness

Each successive movie draws on the conflict of Adrian’s power and weakness. Adrian is never a figure of erotic interest within the films; she remains an unsullied figure of purity which Rocky must protect. Of course, this is a standard situation for women in action films:

“Intrinsically tied in with the necessity for fighting, and therefore for aggression, is the necessity to protect ‘a good woman’. The wife is both to be protected from other men… and to be protected from the ‘streets’…” (Burgin, 1986 :172)

Therefore Rocky expresses his rightful aggression by protecting her from her brother’s abuse, from poverty, and from Clubber Lang’s sexual advances in Rocky III.

Walkerdine ties the act of physical fighting to the struggle to provide for a family – “it validates trying and fighting and therefore the singular effectivity of bodily strength and the multiple significance of ‘fighting’.” This translates muscular masculinity to mastery of external oppression. (Burgin, 1986: 172)

Yet, returning to Rocky II, Rocky has not opted for this physical fight; he values middle class intellectualism more than working class physicality. He aspires to an office job but is without qualifications, cannot read well, and can only scrape together menial work in an abattoir.

When even this low position is denied him, his last recourse is fighting.

Although disapproving, Adrian becomes the catalyst for the fight by becoming pregnant, presenting Rocky with a new paternal masculinity to live up to. His parents are alluded to in the first film, but now Rocky is forced to become the father figure that he is never seen to have.

Furthermore, Adrian’s disastrous premature labour and resulting coma is brought on by her lifting heavy items at work, which creates severe guilt in Rocky – the very lives of his wife and child have been endangered because of his inability to perform as a natural man, yet his wish to perform this in the only way that is available to him is forbidden by his wife. He is to blame both for failing as well as for trying, as her labour comes on after he has defied her and commenced training for the rematch with Creed.

This crisis becomes crippling and Rocky refuses to train, sitting at his comatose wife’s bedside. As Rocky devotedly reads to her in hospital he continues in following in the way she has provided out of his corporeal trap – by improving his mind. In so doing he shows the dependence of his masculine identity on the woman, acknowledging her power.

At the last moment, Adrian regains consciousness, gives her approval for Rocky to train, fight and win. With the authority thus conferred upon him, Rocky trains harder than before, fights harder than before, and this time, wins in a greater way; not just for himself but for his wife, child, and the world.

This ideology of masculinity is built around the feminine; however, we shall return to review the effects of Rocky’s physical transformation on this feminine appendage.

The Spectator

“In a world ordered by sexual imbalance, pleasure in looking has been split between active/male and passive/female.” (Mulvey, 2009: 19)

The popularity of the heavily-muscled, often near-naked cinematic stars of the 1980s signaled the arrival of an era of “overt and newly acceptable male-on-male looking” (Powrie, 2004: 179), when young men were presented not only with the opportunity to look upon and admire the bodies of other men, but the means to do so without the association with homosexuality.

The sports film delivers this opportunity, as do other popular film genres such as sci-fi/war/police narratives. These categories presuppose the presence of weapons and liberal violence along with the opposition of heroes to larger-than-life villains, dictating the very necessity for the action hero’s incredible physical display.

The muscular bodies of Rocky and his opponents appear, sweaty and stripped to the waist, pounding each other ferociously, after undergoing vicious training regimes seen through montages set to music.

Yet this sexual objectification is diffused by the rational framework of the sports narrative, even more so as the cinema audience becomes the spectator of a spectator sport, watching the audience in the boxing ring as they watch the final match.

Mulvey (2009: 21) explains how the male movie star becomes, not the object of the erotic gaze, but the ego of the spectator as the process of identification with the protagonist occurs. Tasker (1993: 77) acknowledges Richard Dyer’s analysis of the structures of activity that are placed around the male body to thwart the risk of that body becoming feminised through passivity.

Therefore, the possibility of the male body as a landing point for an erotic look from any sex is cloaked.

The female viewer

One says cloaked as opposed to denied because, whether these categories and their conventions exist for vicarious identification, or to ease the plight of the male spectator, one may yet dare to suggest that the spectator may be female.

Unfortunately, within contemporary film theory one often falls back on methods which restrict outcomes to those which have been handed down – that is – that men look and women are looked at.

Walkerdine uses psychoanalysis as the basis of her consideration of Rocky II but argues that “by using psychoanalysis to understand relations within a film and then using voyeurism to understand the viewer, we are left in a sterile situation which assumes that all viewers ‘take on’ the psycho-dynamic of the film as far as it relates to the Oedipal conflict. As Laura Mulvey and others have pointed out, this leaves women as viewers in a difficult position.” (Burgin, 1986: 189)

The intense physical suffering endured by the action hero can be understood as a specific kind of sexual display.

Movies of this period often revel in the portrayal of the hero’s undergoing physical wounding, pain, and vulnerability. Referring to such moments in the Rambo series, Jeffords(1) states:

“On the most straightforward filmic level, such moments rationalize sustained attention to the exposed male body, scenes that, as Steve Neale pointed out some time ago, are sources of anxiety in a Hollywood film tradition in which the female body is usually the exclusive object of erotic desire. Although all three films are devoted almost exclusively to the portrayal of Rambo’s body, these scenes are among the few in which that body is still… Consequently, audiences can examine Rambo here at some leisure and explain any anxieties aroused by that examination as anxieties of plot and not pleasure.” (Jeffords, 1994:50)

Yet this does not elide the fact that there is considerable eroticism lavished on the body on that ‘most straightforward level’, and that this eroticism is often experienced because of the hero’s endurance of pain and not simply coincidentally because the hero’s body is still; here, we are immediately reminded of the erotic iconography of Saint Sebastian.

Without this, how do we understand the abundance of scenes in which the hero’s desirable body is beaten, cut or tortured, yet manages to rise to the film’s triumphant climax? Surely relying on Freudian or Lacanian analysis is a fundamentally flawed approach, using one of the most important tools provided by patriarchy, but instead of making a break, buttressing the edifice of the system.(2)

A different system is needed to avoid returning to phallogocentric discourse, denying the female gaze.

Transformation

On their first date, Rocky shows Adrian his nose, stating that it has never been broken.

It stands as a symbol of pride in resilience, displaying how little he has to show for his efforts, but also his inner worth in the midst of his apparent shortcomings. When he loses his perfect nose to Creed in the climactic match the loss is justified – Creed is the greater boxer and in this instance there is no shame in having this virginity taken by a worthy opponent.

Thus Rocky exchanges this small symbol of personal pride for a far greater one, and the physical transformation describes a liminal transformation.

While this physical crossing of a threshold for the character is important for the first film, it is the transformation undergone by the character’s body over the gap between the second and third films which is of greater interest, precisely because it is an organic transformation, occurring externally to the movie series and being written in Stallone’s body, altering Rocky and the films’ masculine ideology.

From the domestic to the political

The domestic nature of the narrative in Rocky seems to preclude a link to Jeffords’ portrayal of the hard-bodied action hero functioning as a symbol or symptom of Reaganism.

Yet by 1985, Rocky is “pitted against an enemy whose identity and nature makes the hero into an emblem of the national body”, (Jeffords, 1994:53) when in Rocky IV he fights the robotic Soviet fighter Ivan Drago. This remarkable shift – the “bum” fighting for self-respect in 1977 becoming the very emblem of America itself fighting the USSR – was reached due to a sharp change of direction by the point of Rocky III.

The film opens with newspaper and magazine articles charting Rocky’s successes in the ring, and when we see the man himself, we see a new product of the 1980s. His expensive clothes, watch and haircut all mark him as a changed man, whom we learn has been weakened by his success.

It is, however, in his body that the change is quite stunning: Stallone/Rocky has become harder.

The fleshed-out face has given way to chiselled features and sunken cheeks, and his musculature is much more defined – to use the correct terminology – ripped. It appears that once the transition from underdog to champion was made, the external fat – that which was soft, more feminine – surrounding the body had to be expunged. What actually occurred was not, though, simply a concern of plot; what happened was Rambo.

The Rambo effect

Both Rocky III and First Blood were filmed in 1982. Whereas Rocky was an outsider brought inside by social relationships, John Rambo, the hero of First Blood, was an outsider left on the outside.

One operated on the domestic level, the other on the national, but both through Stallone’s body.

The violent sexuality of Rambo’s narrative caused a more overtly sexualised gaze to be exercised in Rocky III. During the scenes in which Rocky and Creed run along the beach in training, the camera glories in close-ups of their muscular thighs (in very short shorts). Finally, we are given the marvelously homoerotic slow-motion sequence of the men celebrating after their run on the beach, jumping in the surf, splashing and hugging one another.

Now Rocky is harder, faster and stronger than ever before, and has truly crossed from contender to champion.

The change in Rocky’s body reflects the change in the films’ female voice. Although still a passive character, when Adrian does speak, it is to shriek a melodramatic speech at Rocky wherein she persuades him to fight once again, but this time for himself alone.

“How’d you get so tough?” he asks, to which she replies, “I live with a fighter.”

Not only has the male hardened externally, but the female has hardened internally. The decade’s performance of hardness slices away the feminine appendage to create a singular, streamlined masculinity, all encased in an impregnable hard body with no added fat.

Yet, because Rocky does not fight in the way that Rambo does, this shared body must be displayed in a different way.

Heavy-duty signifiers

Hence, we are presented with ever larger and more outrageous opponents, all caricatures of hypermasculinity, which the hero must match and defeat. Rocky’s weakness now stems from his relationships to other men – the deaths of Mickey and then Creed, who each serves successively as his trainer/father figure/friend. He must first overcome his emotions and then avenge their deaths, achieving both of these through beating other men.

This reaches its peak in the figure of Drago, a giant man so stripped of any trace of weakness/femininity that he is effectively a machine.

The scenes which see Rocky preparing for this fight amazingly call on an array of signifiers to express his superior masculinity: not only does he grow an impressive full beard, but he trains outdoors in the Russian winter, using the most basic, makeshift equipment, whilst his foe trains under artificial conditions in a state-of-the-art gym. The hero then scales a snow-covered mountain in his pursuit of physical and mental preparation, demonstrating not only his natural masculinity, but that he has actually conquered the natural world.

Ultimately, this performance could not be maintained, and Rocky V was an unsuccessful attempt to return the character to its roots, wounding the now too-hard hero by stripping him of his money and health, returning him to his old neighbourhood and even to his old clothes, focusing on the father-son relationship.

Only with the final wound of aging does the focus on the feminine fully return – and this has to be achieved by the drastic step of cutting away the woman entirely. In Rocky Balboa, we learn that Adrian has died, and it is the internalisation of the pain/the woman, that rescues the character and returns it to critical acclaim.

Conclusion

Much more can be said about the series’ projection of its masculine ideology and its effects on culture; this essay serves merely as a brief introduction to some of the concepts which may be explored through the medium of the films and their place within the “innumerable copies of masculinities floating around in culture”. (Reeser, 2012: 18)

Just as this character’s performance of manliness rose from previous manifestations, it has spawned countless copies and tributes; so at the risk of enforcing what may be decried as an unnecessary intellectualisation (3), Rocky may be posited as a text worthy of in-depth critical analysis.

Notes

- Jeffords’ aim is to draw parallels between the hero’s hard body and the ‘national body’. These examples are used within the ‘national body’ metaphor, to show that past wounds can be overcome and survived through self-repair – but that as this process is unimaginable and unbearable by the individual man in the cinema, the nation’s weakness is in fact weakness at an individual bodily level. (Jeffords, 1994:52)

- Laura Mulvey describes this as “…the ultimate challenge: how to fight the unconscious structured like a language (formed critically at the moment of arrival of language) while still caught within the language of the patriarchy? There is no way in which we can produce an alternative out of the blue, but we can begin to make a break by examining patriarchy with the tools it provides, of which psychoanalysis is not the only but an important one.” (Mulvey, 2009: 15) As for Walkerdine, her approach is “to analyse the constitution of subjectivity within a variety of cultural practices”… asking “how people make sense of what they watch and how this sense is incorporated into an existing fantasy-structure”, (Burgin, 1986: 192) the basis of which is to be found in Freud’s analysis of dreaming.

- Both Tasker and Walkerdine are against “the ‘intellectualization of pleasures’ which seems to be the aim of much analysis of mass film and television.” (Burgin, 1986: 168)

Bibilography

Brennan, T. (ed). 1989. Between Feminism And Psychoanalysis. Routledge. UK

Burgin, V. et al. (eds) 1986. Formations Of Fantasy. Routledge. UK

Darwent, C. 10/02/2008. Arrows of desire: How did St. Sebastian become an enduring homoerotic icon? The Independent. available online at: http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/art/features/arrows-of-desire-how-did-st-sebastian-become-an-enduring-homoerotic-icon-779388.html accessed 07/11/2012

Jeffords, S. 1994. Hard Bodies: Hollywood Masculinity In The Reagan Era. Rutgers University Press. New Jersey, USA

Powrie, P. et al. (eds) 2004. The Trouble With Men: Masculinities In European And Hollywood Cinema. Wallflower Press. UK

Mulvey, L. 2009. Visual And Other Pleasures. Palgrave Macmillan. UK

Reeser, T. W. 2010. Masculinities in Theory: An Introduction. Wiley-Blackwell. UK

Tasker, Y. 1993. Spectacular Bodies: Gender, Genre And The Action Cinema. Comedia. UK

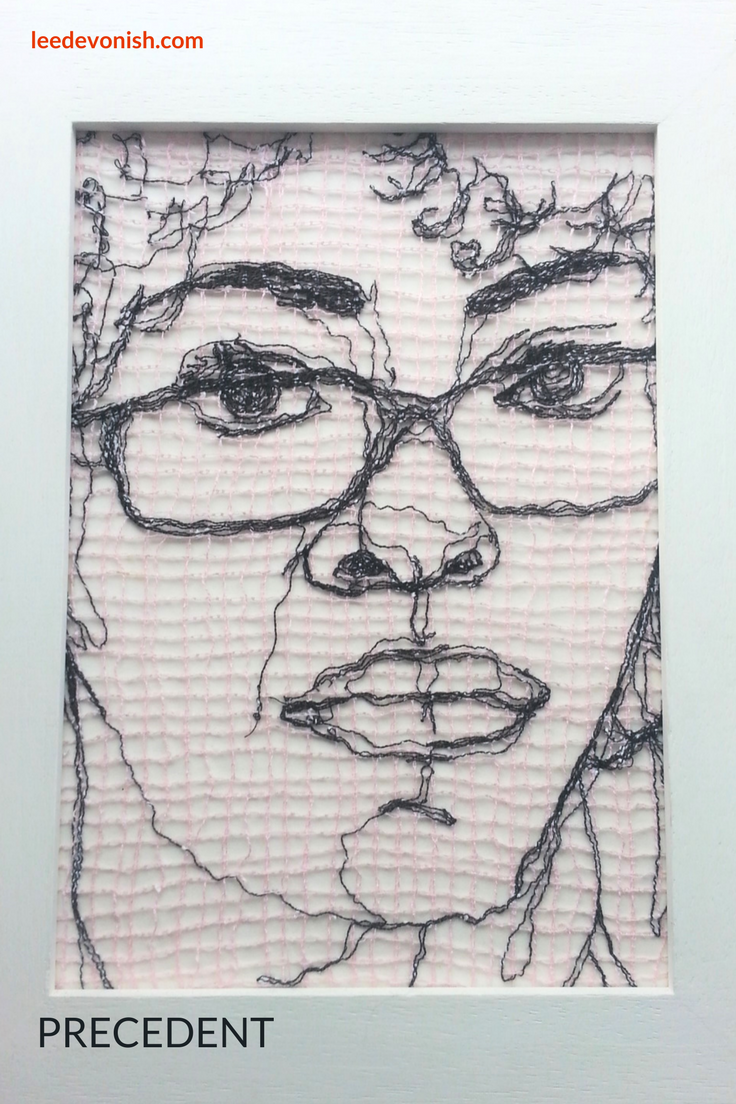

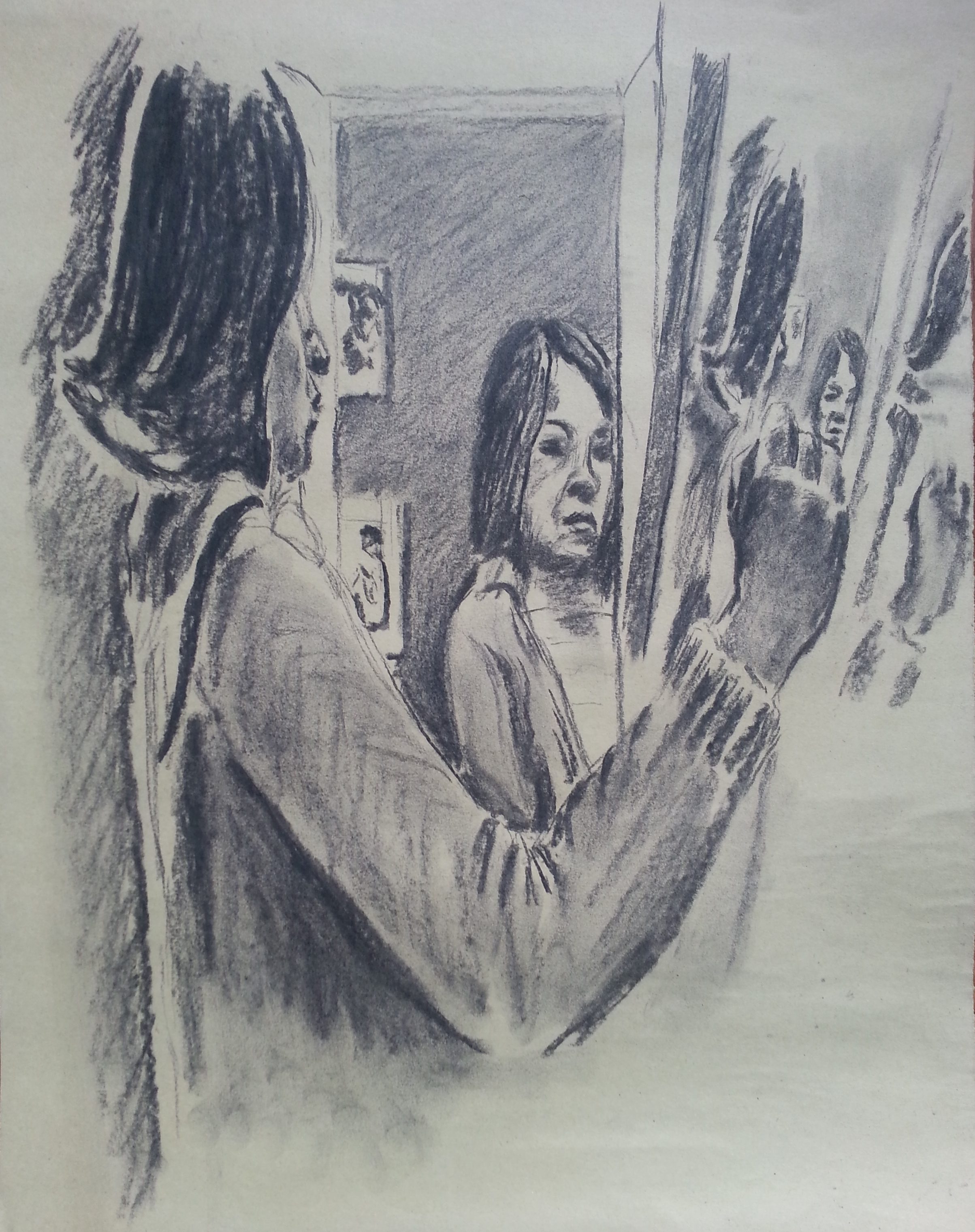

Related artworks

My earlier work clearly dealt with issues surrounding the depiction of the male form in fine art, but this particular subject has directly informed my “muscle series”, including Fight, pictured below.