Visual Research and Working Methodologies: An Essay

The following text has been adapted from my student essay for the “Visual Research and Working Methodologies” module of my BA (Hons) top-up course undertaken in 2011.

Looking back over student work is a curious exercise; it feels strange to have communicated so earnestly, and so formally at the same time. Here it goes…

Visual Research and Working Methodologies

The intention for the work this year is to investigate the depiction of the male figure in contemporary art through the creation of a larger body of work, to be realised in the form of paintings and carved wood sculpture.

Several artists whose practices have been referenced are Ricky Swallow, Ana Maria Pacheco, Clive Head, Ellen Altfest, Patrick Hughes, Tomoaki Suzuki, Gehard Demetz and Willy Verginer.

The depiction of the male figure in contemporary fine art arose as a theme in the middle of the previous academic year, after the completion of several paintings and drawings of the artistʼs male friends. The attention they attracted, particularly from female viewers, posed the question of why in the post-feminist age the nude was still almost exclusively female, and why both male and female artists and viewers expected or preferred to see females as objects of art.

The paintings completed at the end of the year were meant to explore the reaction of the viewer to male subjects, presented as objects of beauty, and to question the assumed gender of the gaze.

The combination of two and three dimensional mediums is an important part of the development of the practice. Spanish devotional sculpture from the middle ages has recently come to the fore in terms of an historical precedent in bridging the gap between painting and sculpture, and in researching contemporary polychromed wood sculpture, the work of Ana Maria Pacheco and Tomoaki Suzuki has been of particular interest.

Ana Maria Pacheco is an artist who moves fluidly between various mediums, finding solutions to problems in one medium through working in another. (MacGregor, 1999. p.5) Pachecoʼs painted wooden figures are relevant to this research, as her aesthetic philosophy is found to be very appealing and sympathetic. She reflects that her colonial background may be the cause of her preference for her work to be well finished; she says,

“there is this thing about spontaneity, very closely connected with modernism, I find it impossible.” (Wiggins, 1999. p. 47)

Patrick Hughesʼs work as viewed in his retrospective exhibitions at the Flowers galleries in London was provocative, not in the direct way of manipulating perspective, but in his combination of highly realistic painting and 3-dimensional support. Reflecting on Hughesʼs work in the light of the recent interest in combining sculpture and painting, the synthesis seems entirely natural and very exciting. One method of working towards this combination is to utilise supports in circular and oval shapes instead of the traditional rectangular format, as have artists such as Frank Stella. Exploiting the cultural references of the circular and oval format will be a key aspect of the work within painting.

The work of Northern Renaissance artists including Holbein the younger has long provided an inspiration to attempt a similar effect of smoothness of surface, with the removal of the evidence of the artist.

The latest oil paintings, [redact]Tobi[/redact] (fig. 1) and [redact]Phil[/redact] (fig. 2) have shown an inclination towards this surface quality, but there is some way left to go in deciding how much of the brushstroke should remain, and how much mimetic illusion is aspired to. The effect of the artistʼs touch, the sensual effects of the paint surface and how much this affects the reception of the image in the mind of the viewer, is of great importance. On reflection, these last paintings produced have appeared static and overly slick in comparison to previous work, in particular [redact]Cill[/redact] (fig. 3)

A consolidation of style is therefore a key aim in production of this new work.

Since seeing the work of Clive Head at the National Gallery in London, the ambition has been to move the work towards a more detailed, photorealistic style. Some progress towards this was made in the last paintings, but there is much more progress to be made in terms of technique.

The hyperrealist work of Ellen Altfest at her exhibition “The Bent Leg” at White Cube, Hoxton, was a later discovery, and thematically is closely aligned to the current investigation of masculinity. Altfest similarly cites Sylvia Sleigh as an influence, and although in terms of painterly technique, her works are more thickly layered and heavily encrusted, the focus on detail is an essential link. (Storr, 2011)

Referring to Ricky Swallowʼs hyperrealistic sculpture Paton writes:

“we tend to associate detail with clarity, and conversely to think of blur and vagueness as the outward signs of mystery. In Swallowʼs art, however, detail is not an antidote to mystery but a form of it – a way to delay recognition, to make strange, to enlarge an object in a viewerʼs mind.” (Paton, 2004. p.10)

This view of detail as a form of mystery is a striking concept which encourages an interest in smaller sized, more detailed objects –

“Swallow is less interested in how loud an artwork can speak than how closely it can make you listen.” (Paton, 2004. p.64)

The intention is to expand further into a wider range of sizes, and produce a greater number of smaller paintings as a way of pushing the working methods. Since starting to exhibit and to enter work into competitions and open calls, the presentation of this current work has become a prime concern.

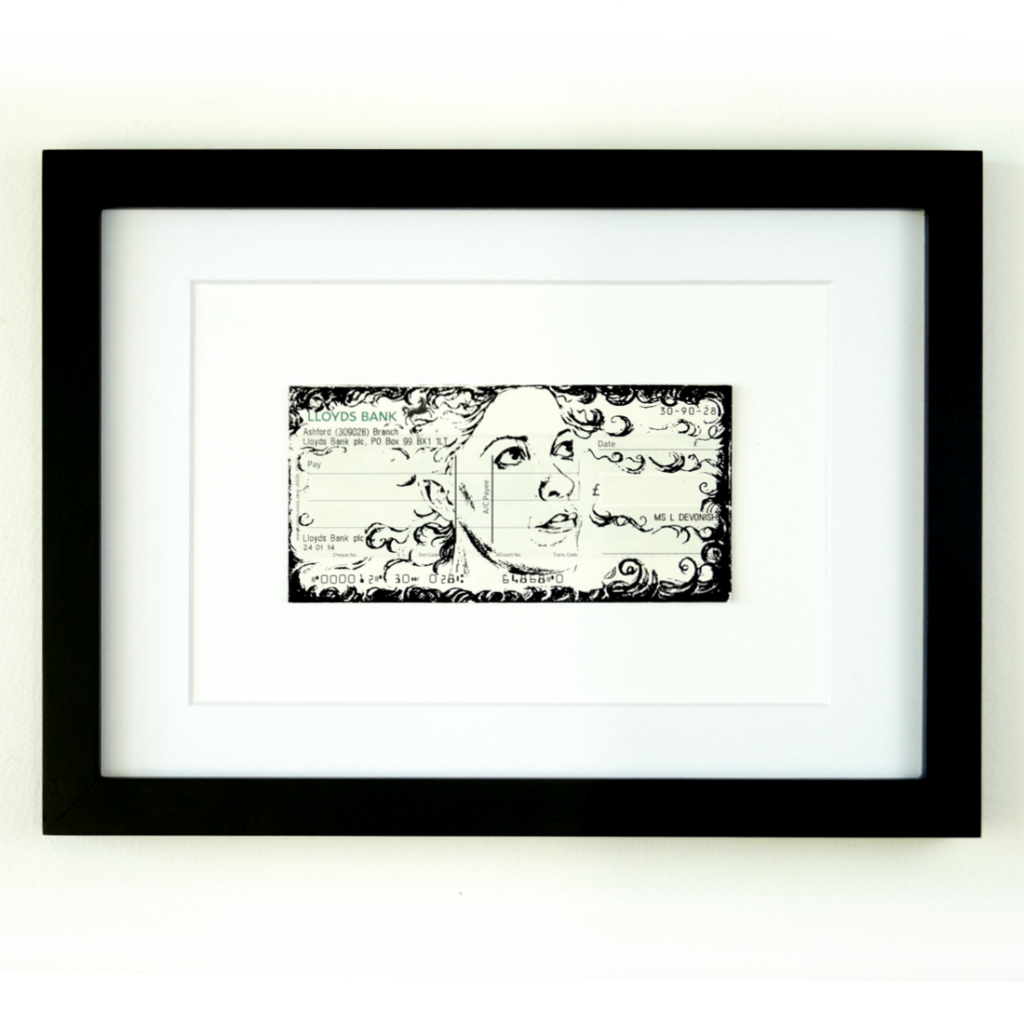

The impact that something as simple as framing has on the perception of a piece is a key area of interest and influences the choices made for the presentation of the work. Its usefulness as a method of contextualising images of men lies in how framing creates importance around an artwork, and how framing could create an artwork in itself. The frames will be used to present the images of men as works of art, to validate them as art by placing them in a very traditional sphere by presenting them as women traditionally have been.

The treatment of the frame as an integral part of the artwork incorporates the element of form within the 2-dimensional discipline, once more providing a link between the pictorial and sculptural.

Suzukiʼs use of scale, presenting his sculptures 1/3 life size, is something that sets him apart from other artists working in wood, and confers a very engaging quality to the pieces. Gehardt Demetz and Willy Verginer are both Italian artists carving naturalistic figures in limewood, and like Suzuki and Swallow they utilize virtuoso carving techniques which inspire emulation.

Suzukiʼs method of carving and painting is very interesting; he works towards a high level of detail, using photographs taken from 360º and carves very close likenesses. Yet his figures are not smoothed to the extent that Swallowʼs are; there remain traces of the tools, slight angular planes on the surfaces. He uses acrylic paint on limewood, but does not seem to use gesso to prime the wood. Perhaps because of this the skin colours can appear to be flat – especially when the subject is black. The paint appears chalky, and some of the wood grain remains visible through the paint, which hints to the process in the same way that the carving does. In contrast, the highly refined process of gesso application in traditional Spanish devotional sculpture lends a more naturalistic ground, and produces effects which are closer to the desired result for the artwork.

Whether the painting or sculpture is concerned with image or form, a predominant theme is that of “re-skilling”, connecting to traditional aspects of production and increasing technical fluency. The aspiration towards technical mastery that wood carving as a craft instills is obvious at amateur levels, as contemporary carversʼ societies show; this is a legacy of artists such as Grinling Gibbons.

The V&Aʼs Power of Making exhibition highlighted the debt that oneʼs attitude to working owes to oneʼs experience in design and craft. The exhibition focused on craft, on “objects that relate not to the quick invention of conceptual art, but to the slow perfection of skill”. (Miller, 2011. p.20) The line at which craft meets fine art is perennially an interesting one to define, especially within the discipline of wood carving.

“ʻCraftʼ is still a charged, even scandalous, term in the end of the professional art world that Swallow inhabits… There arose “a view of craft-skill as a kind of excess in artʼs economy of ideas – something ʻgratuitousʼ.” (Paton, 2004. p.95).

One of the ideas behind a traditional, skill-centric approach is an attempt to elicit a feeling of trust from the viewer.

“The care that we take in making something properly is cousin to the care that we retain for other people and their labour…selecting depth at the expense of breadth” (Miller, 2001. p.22)

It is important that the viewer feels able to trust the artist and thereafter become immersed in the discourse started by the artwork. In addressing the gender of the gaze, the viewer-subject connection and relationship becomes an essential aspect of the work, and this is established by the formal methods of production.

Figures 1, 2 & 3 are studen works, all now destroyed.

Bibliography

Adler, K. (7-24) 1999. in: Ana Maria Pacheco In The National Gallery. ed. Jervis, J. National Gallery Publications. UK

Bray, X. 2009. The Sacred Made Real: Spanish Painting And Sculpture 1600-1700. National Gallery Company Ltd. UK

Jopek, N. and Marqués, S. 2007. in: The Making of Sculpture: The Materials And Techniques of European Sculpture. ed. Trusted, M. V&A Publications

Langland, T. 1999. From Clay To Bronze: A Studio Guide To Figurative Sculpture. WatsonGuptill Publications. NY USA

MacGregor, N. [ps2id id=’MacGregor’ target=”/]1999. in: Ana Maria Pacheco In The National Gallery. ed. Jervis, J. National Gallery Publications. UK

Miller, D. [ps2id id=’Miller’ target=”/]2011. The Power Of Making. in: Power of Making: The Importance Of Being Skilled. ed. Charney. V&A Publishing

Paraskos, M. 2010. Clive Head. Lund Humphries. UK

Paton, J. [ps2id id=’Paton’ target=”/]2004. Ricky Swallow: Field Recordings. Craftsman House. Australia

Storr, R. [ps2id id=’Storr’ target=”/]2011. Ellen Altfest: The Bent Leg. White Cube. UK

Slyce, J. & Hughes, P. 2005. Perverspective. Momentum. UK

Wiggins, C[ps2id id=’Wiggins, C’ target=”/]. 1999. in: Ana Maria Pacheco In The National Gallery. ed. Jervis, J. National Gallery Publications. UK

Williamson, P (ed). 1996. European Sculpture At The Victoria And Albert Museum. The Victoria And Albert Museum. UK

Web references.

Corvi-Mora. accessed Nov. 2011. http://www.corvi-mora.com/tomoakisuzuki.php

Demetz Website. accessed Oct. 2011. http://www.geharddemetz.com/

Hada Contemporary. Cha Jong Rye. accessed Oct. 2011. http://hadacontemporary.com/cha-jongrye/

Leo Koenig Inc. accessed Oct. 2011 http://www.leokoenig.com/exhibition/view/694

Meneghelli, L. accessed Oct. 2011 http://www.whiteroompositano.com/english/willyverginer-text-by-l-meneghelli/

Moore, S. 2009. “Open Frequency: Tomoaki Suzuki”. Axis. accessed Oct. 2011 http://www.axisweb.org/ofSARF.aspx?SELECTIONID=20469

Pratt Contemporary Art. Ana Maria Pacheco. accessed Oct. 2011. http://www.prattcontemporaryart.co.uk/ana-maria-pacheco-2/