What should I paint?

The question of subject is one that constantly reoccurs to me:

What should I paint?

Why do I want to create a work about this?

Should I?

Is it worthwhile?

What will everyone else think?

Having a sense of self consciousness is vital to thinking critically about my own work, but I may just be the kind of person who thinks themselves out of action.

Usually what I consider the most successful work comes about when I stop obsessing about the reasons I feel interested in something and simply explore the idea.

Give yourself permission to experiment… and fail.

The major editing has to take place during the creation, or even afterwards, or else I have the tendency to talk myself out of every idea. This excess of thought is probably what kept me away from painting for many years. Only since I have given myself permission to fail have I been able to see results.

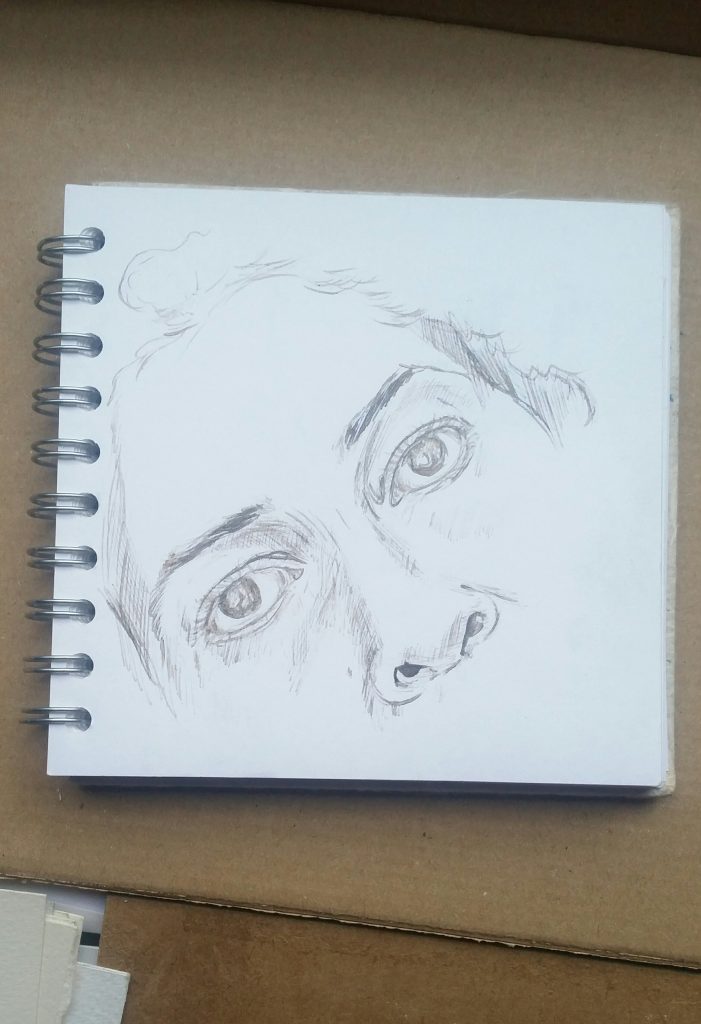

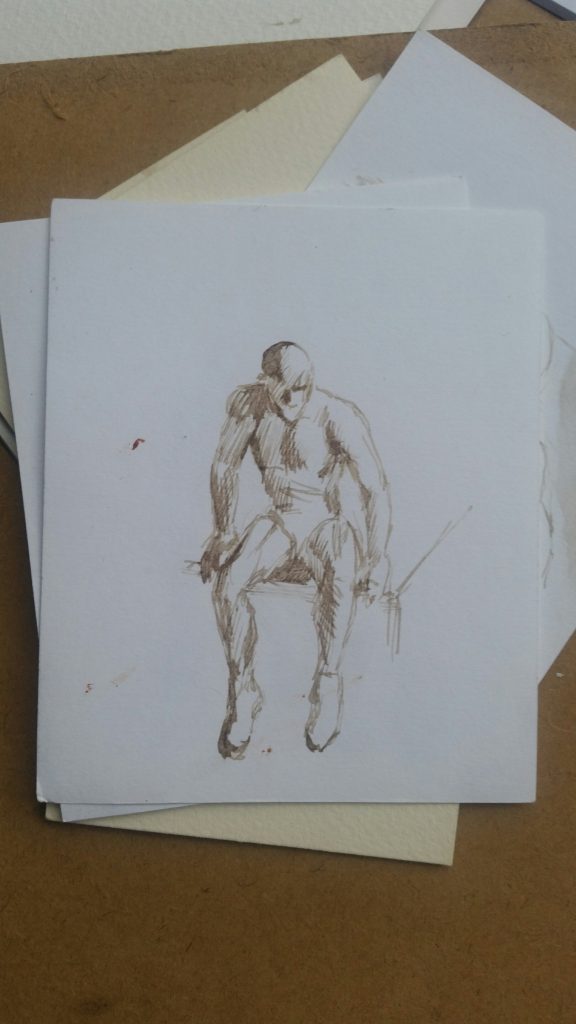

Having a visual record of a thought gives me a chance to assess its strengths, weaknesses and future development… and these infantile records often come to have their own lives independent of whatever work they may have triggered.

You only figure out what you should be painting by trying a bit of everything.

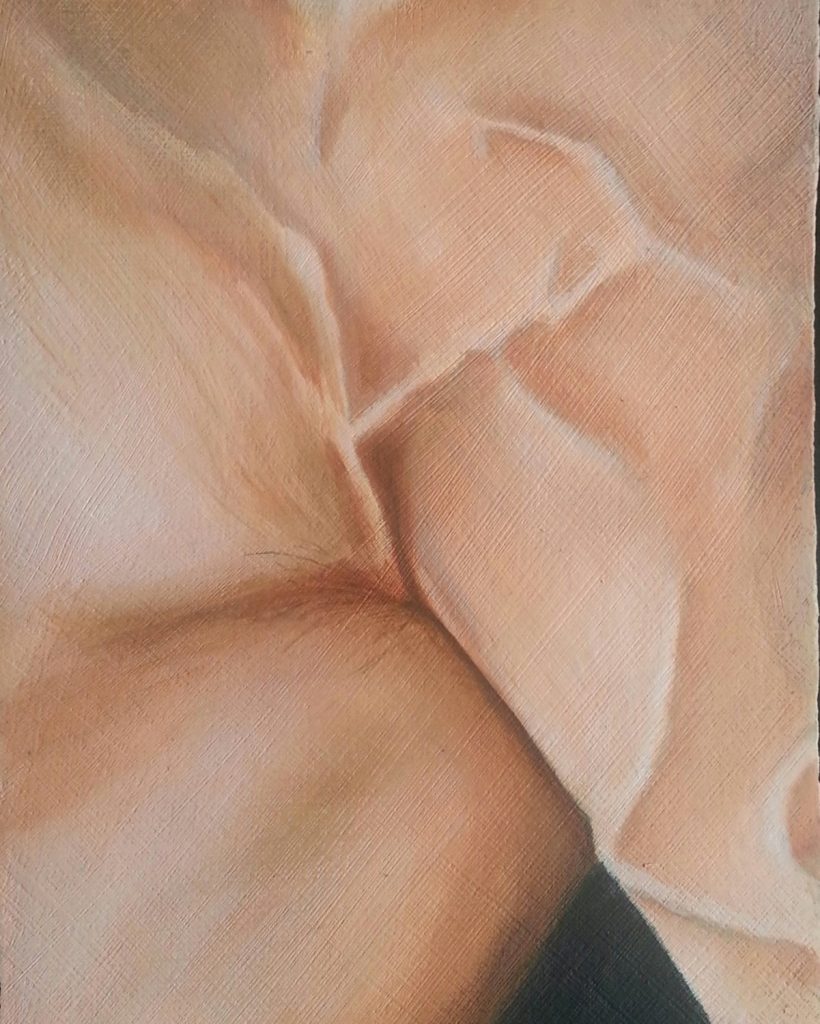

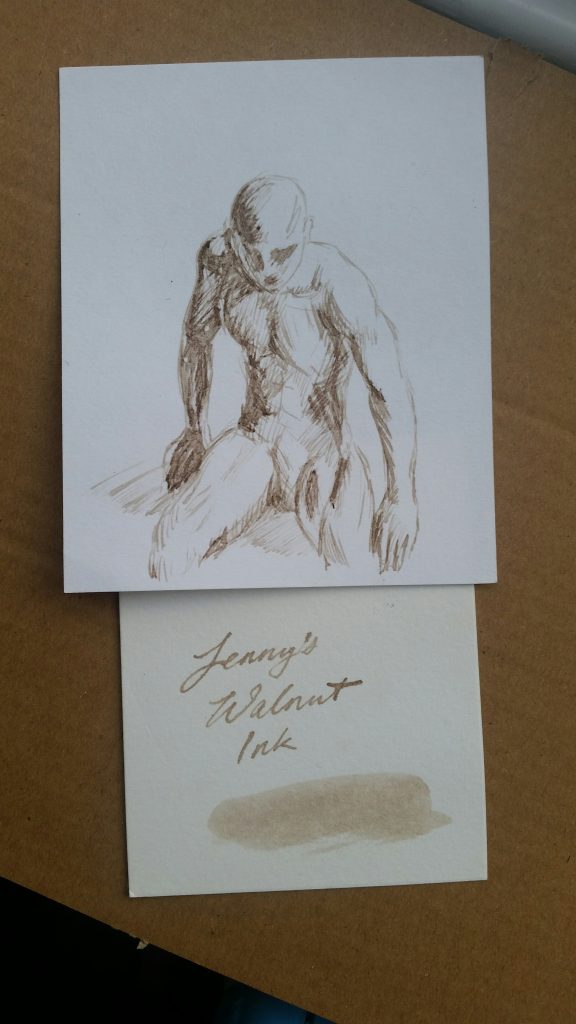

Over the years, because of knocking around and trying different things, I’ve realised that I gravitate towards depicting the human figure, and that everything surrounding exists in its orbit. The landscape exists because it is viewed by the person. The objects have been arranged by, or carelessly left behind by someone, who may reappear at any moment. Although the places, rooms and objects hold their own value, it is the people populating the spaces I return to instinctively.

Just how to use this, now, is the thing I’m continually working at.

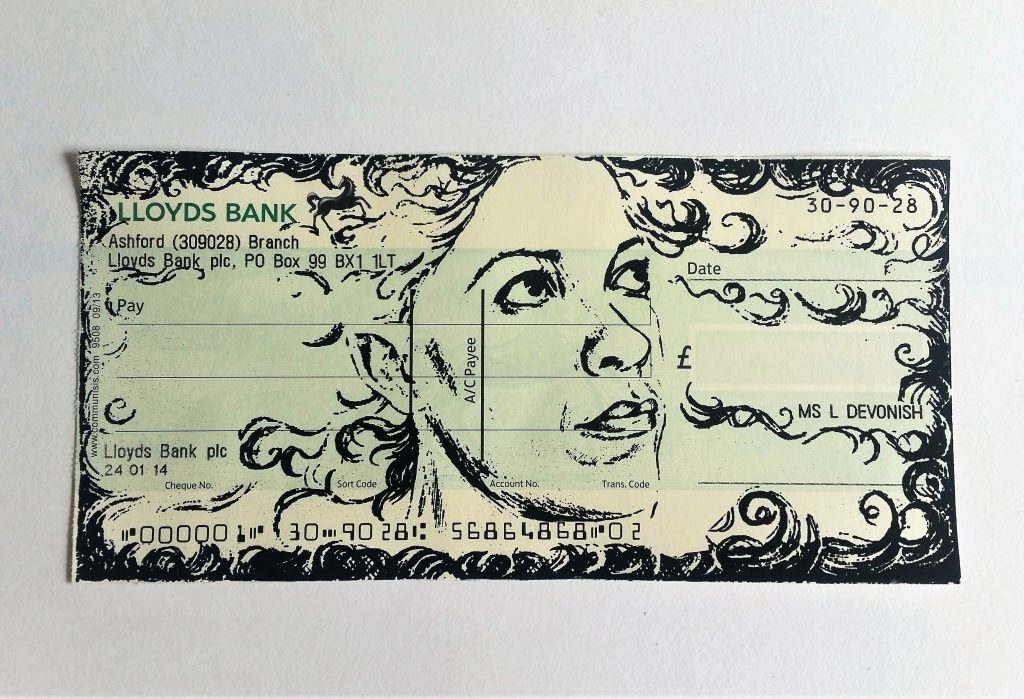

The world outside of the figure

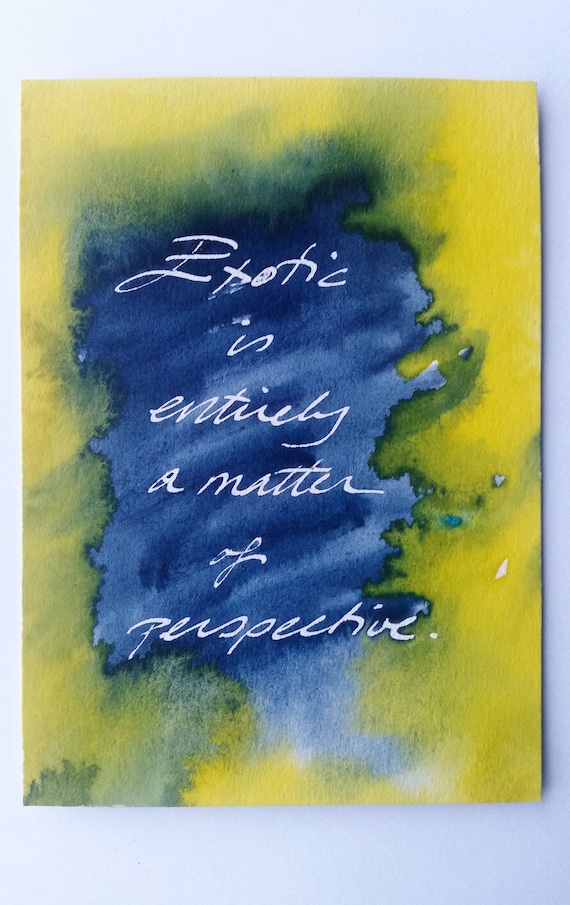

Of course, not all of my work revolves around painting portraits; some of my recent text-based prints focused solely on handwriting and colour. It’s possibly a strange departure, but when I consider how much a part of me my writing is as well, the text pieces are a natural progression of my words flowing into the visual.

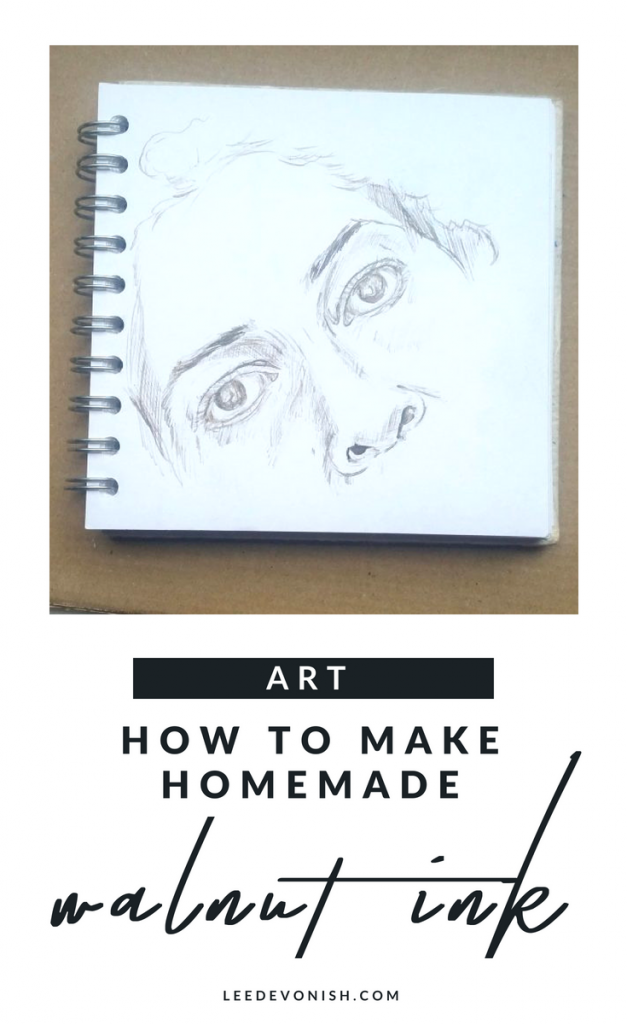

Why I paint portraits…

I love examining the nuances of faces, and the angles and relation of each part to the next. Portraiture has fascinated me since I was a child. The capacity to render another person’s likeness is a tremendous thing to discover as a young person, but the discovery that that capacity in itself is not enough, is even more so. That’s what spurs you on to make art.

When a painting is finished, and it represents many hours of contemplating another person’s face, attempting to conjure up some representation of their personality, you are left with the realisation that it is incredibly fragile.

What should I paint?

I should paint the idea I can’t do without. Here’s what it is for me:

A portrait – a depiction of a human being – can lose its meaning in a second, all because of what the subject does, or perhaps no longer does. The person changes continually whilst their image remains the same. It will never remain an accurate representation of that person; it can only be a representation of a subject at a single point, as seen through the mind of the artist.

It’s an exchange between two people who will never be the same two people again.Then, when either the artist changes her mind, or the subject changes himself (or is unwillingly/unknowingly changed), that representation can crumble into something quite meaningless.

That brief glimpse of meaning is what I want to paint.

What should you paint?

Ultimately it’s the meaning of the object or image, more than the object or image itself, that will give your work purpose and lead you on to the next step of your work. Start with something – anything – and mess around until you know what you don’t want to paint and what you want to.

The next time you think, “what should I paint?”, think about it as, “what do I want to say?”