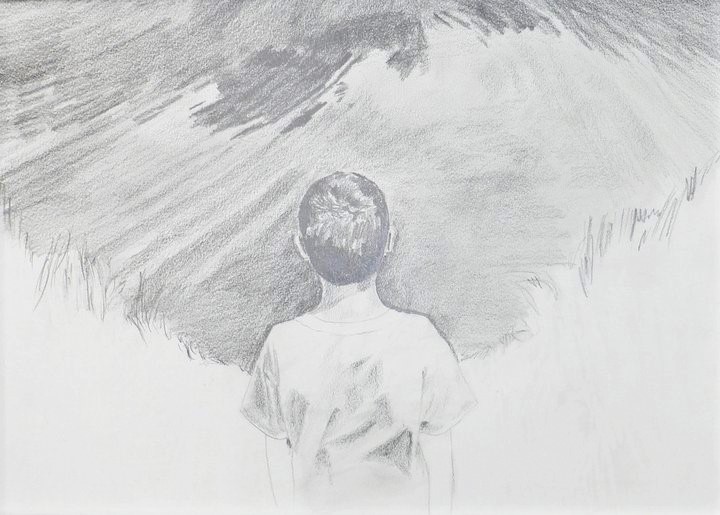

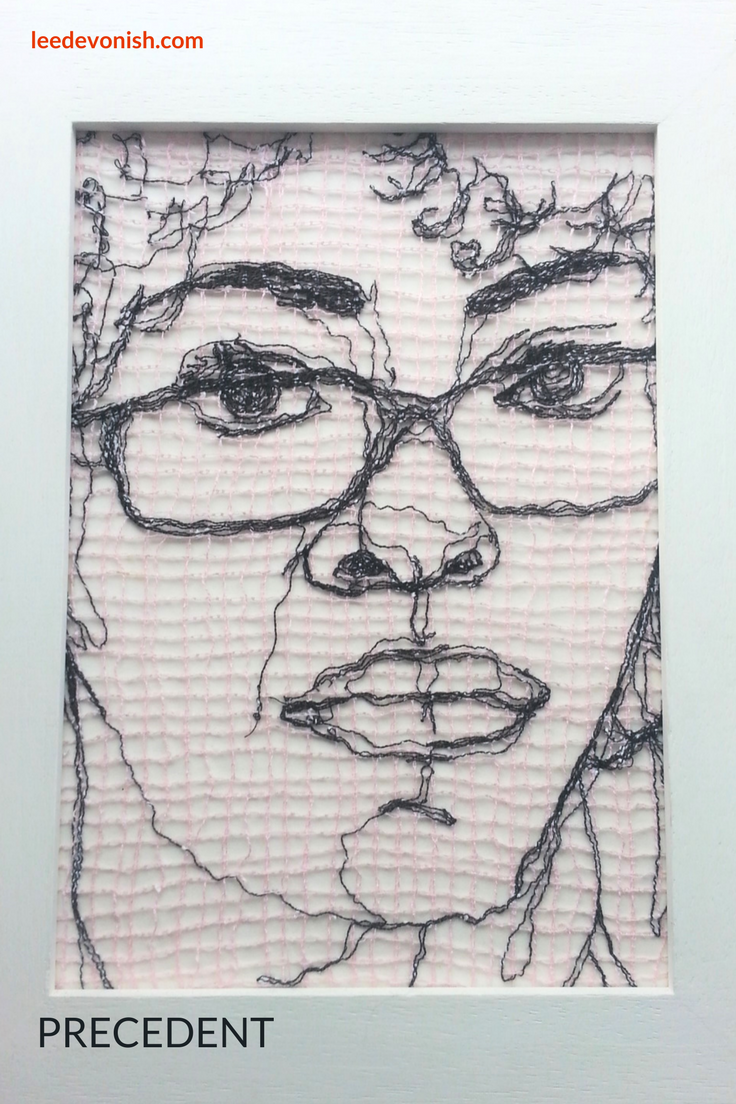

Precedent

The story behind this drawing – a piece that is unique in my practice – is simple; it was made purely from a need to try. It was based on an old sketch I had done a decade before, and as I had changed so much in the intervening time, it felt fitting to revisit that image and make it into something more meaningful.

The title – Precedent – refers directly to the original drawing that preceded it, but also to all of the time I had spent sewing to try to earn a living as a single parent, setting the precedent for working with polycotton thread.

Experimenting

One essential part of my working method is to indulge my curiosity, to break away from my preferred media and experiment with materials.

Textiles

Monochrome prints are a traditional extension of my drawings, but although drawing in yarn and thread may appear to be a digression in style, they hold much expressive potential. The physical process of puncturing canvas or fabric with a bodkin, and the deliberate placement of line, can create a real energy and tension in a yarn drawn piece.

Machine stitching

Machine stitch drawing seemed to be a natural interpretation for a sketch of myself I had done just before marrying and moving to another part of the world.

Thread was the most apt vehicle for depicting the intervening years, which had been largely spent immersed in textile work. The commercial connotations of the thread as well as the process of machine stitching tell their own story, and juxtapose with the colour and expression of the figure.

Finding the right materials to create a shortcut to a narrative is extremely rewarding.

Interdimensionality

Consisting of lines with no substrate fabric or ground, the drawing and surface are one and the same. The delicacy of the mesh and fragile lines, which can move slightly within the grid, give an air of sadness and loss to this drawing.

Mounted away from a surface, the threads cast shadows, line and background become one, and the two dimensional drawing becomes sculptural.

I like the fact that, without its frame, this piece could simply be crumpled or folded like any other fabric. Its flimsiness as well as its hidden strength as an interconnected fabric makes me think of it as a metaphor for life, and not just my own.